Quarry Economics - Stone Production

and Cost in the Past

- Deterioration, Weathering, & Preservation of Stones

- Economic Factors in Granite Quarrying - 1908

- Economic Classification of New England Granites - 1923

- Economic Classification of the Chief Commercial Granites of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island - 1908

- Commercial Value of the Granites - 1908

- Production of Granite by States - 1923 (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island)

- Other Economic Considerations

- Economic Census

- Use of Stone in Buildings, Paving, etc.

-

Deterioration,

Weathering, & Preservation of Stones

- The Cause and Prevention of the Decay of Building Stone (May 1887) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 19, Issue 5, May 1887, pgs. 107-108. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Causes of Decay in Building Stones (part II) (September 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 9, September 1891, pg. 206. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

-

Conservation - Friedrich Rathgen: The Father of Modern Archaeological Conservation, by Mark Gilberg, from the Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, JAIC 1987, Volume 26, Number 2, Article 4 (pgs. 105 to 120) (The site copyright is to American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works.)

- Decay of Stone (November 1893) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 25, Issue 11, November 1893, pg. 225. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Destruction of Building Stone (January 1888) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 20, Issue 1, January 1888, pg. 12. (Includes a sketch of the Hallowell, Maine, granite quarry; article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- The Disintegration of Marble (February 1888) Quarrying Notes- The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 20, Issue 2, February 1888, pg. 35. (Mentions Gerard College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Disintegration of Marble (October 1888) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 20, Issue 10, October 1888, pg. 228. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Preservation of Stone (February 1888) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 20, 20, Issue 2, February 1888, pg. 36. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Preserving Stone (August 1892) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 24, Issue 8, August 1892, pgs. 182-183. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Process for Preserving Building Stones (November 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 11, November 1891, pg. 254. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- To Clean Marble (December 1884) Quarrying Notes - The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 16, Issue 12, December 1884, pgs. 275-276. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- To Clean Marble (October 1886) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 18, Issue 10, October 1886, pg. 228. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Weathering Stone (February 1887) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 19, Issue 2, February 1887, pgs. 34-35. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Why Snow Destroys Marble Statuary (September 1887) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 19, Issue 9, September 1887, pg. 204. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

-

Economic Factors

in Granite Quarrying - 1908 The following

discussion is quoted from The Commercial Granites of

Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island, Bulletin

354, by T. Nelson Dale, published in 1908.1

The factors upon which the successful operation of a granite quarry depends are various. The first are petrographical and geological. These include (1) the mineral composition and texture of the rock and its physical properties; (2) its structural features-that is, the directions of the flow structure, rift, and grain, compressive strain, and contact surface with overlying or adjacent rocks of other kinds; (3) the character of the sheet structure, of the jointing, and the headings, dikes, and veins; (4) the size and number of inclusions and "knots," and (5) the thickness of the rusty rims of sheet and joint surfaces. The economic importance of minute structural features, such as the great variation in its fissility, is exemplified in the range of the number of paving blocks which equally skilled workmen can make of different granites in one day. Thus at Quincy a paver averages 75 blocks a day (size, 12 by 8 by 4 inches). In Maine the number is from 80 to 100 of New York size (11 to 14 by 7 by 4 inches). At Milford, N. H., the average number of Philadelphia size is 200, and at Redstone, N. H., 130 of New York size, which is from 33 to 50 per cent more than is usual in Maine. At Becket (Chester), Mass., the average is 150, size not stated. Another geological factor is the "stripping" or amount of surface material, sand, etc., to be removed from the granite surface.

Other factors, such as facilities for drainage and water supply, the location of the quarry with reference to transportation facilities by land and water, and the disposal of waste, are hydrographical and geographical.

Then there is the artificial factor: The equipment of machinery for pumping, drilling, hoisting, loading, and transfer to car or ship. In the larger quarries this includes air compressors and air drills and in places stone crushers for the utilization of waste.

But when all these factors are satisfactory, success will still largely depend upon the experience and judgment of the foreman or superintendent who directs the blasting and splitting. Without his intelligent control, suitable stone, favorable natural conditions, adequate capital, equipment, and labor are of little avail. The selection of the place for blasting, the size and shape of the hole, the selection of the powder, and the size of the charge are all matters requiring careful consideration. The thickness of the sheet, the proximity of joints, the vitreousness of the stone, its rift and grain structure, the physical laws governing the action of explosives, and the direction in which the quarryman desires to split the mass are all factors in each problem.

The principles of rock blasting are set forth mathematically in a recent book by Daw,2 and a general description of quarry methods will be found in a report by Walter B. Smith. .3

A difference is found in blasting and splitting granite in winter and summer. A low temperature increases its cohesiveness, but, probably in connection with water, increases its fissility where the "rift" is feeble.

It is reported that in quarries in Finland the expansive power of freezing water is regularly used in splitting. This is in line with the ancient Egyptian use of the Expansion of wet woody tissue. A method of blasting in use in some of the English coal mines by means of the expansion of slaked lime may be susceptible of adaptation to the quarrying of the more delicate granites.4

In this connection should be mentioned the method, recently adopted in the granite quarries of North Carolina, of developing an incipient sheet structure by the use of high explosives followed by the application of compressed air.

-

Economic Classification

of New England Granites - 1923 5

The following discussion is quoted from The Commercial

Granites of New England, Bulletin 738, by Dale, T.

Nelson, 1923. (I have changed the format from a paragraph

to a list so the classes can more easily be

distinguished.)

"The granites of New England in respect to their general uses may be divided into nine classes:

(a) constructional, used for buildings, bridges, retaining walls, pedestals;

(b) monumental, used for monuments, and requiring finer texture than those of class a;

(c) sculptural, used for delicate carving and statues, also for monuments;

(d) inscriptional, adapted to inscriptions legible at a distance;

(e) polish, susceptible of high polish;

(f) rusty-faced, for buildings requiring special contrasts of color;

(g) curbing and trimming, adapted by their gneissic texture for curbing, trimming, and sills;

(h) breakwater, easily quarried and situated at tidewater, and thus adapted to the construction of breakwaters;

(i) paving, suitable by their rift and grain for the manufacture of paving blocks.

As the waste of some constructional and monumental granites is also used for paving, any enumeration of paving-stone quarries would be misleading. The quarries on the Maine coast and on Cape Ann, Mass., are the chief producers of paving blocks."

-

Economic

Classification of the Chief Commercial Granites of

Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, published

in 1908 6

(See linked tables pages 211 - 212) -

Commercial Value of the

Granites - 1908 7

The section below is quoted from The Chief Commercial

Granites of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island,

Bulletin 354.

"These granites represent quite a range in commercial value-from 25 cents to $3.25 per cubic foot. The following prices were obtained from the larger concerns as current in 1906. All are f.o.b. and per cubic foot in the rough.

"Constructional granites-Milford, Mass., pink, in blocks up to 10 tons, $0.60 to $0.70. Foundation and bridge rubble work, $0.25. Quincy, light, for bases and hammered work, ordinary sizes, $0.50 to $0.85. Extra light, for bridge work, without reference to size, $0.35. Rockport, gray, ordinary sizes (3 to 15 feet long, 1 ½ to 4 feet wide, and 1 ½ to 3 feet high), best quality, $0.50. Concord, blocks under 9 square in base, $0.60. Redstone, N. H., red, ordinary sizes, $0.40 to $0.50. Milford, N. H., dimension stone in blocks up to 100 cubic feet, $0.40. Westerly, red, ordinary sizes, $0.60.

"Monumental granites-Quincy, medium, in blocks up to 40 cubic feet, $1 to $1.10; 40 to 55 cubic feet, $1.15. Dark, in blocks up to 40 cubic feet, $1.30 to $1.35; 40 to 55 cubic feet, $1.40. Extra dark, in blocks up to 40 cubic feet, $1.60. Becket (Chester), in blocks up to 40 to 50 cubic feet, $1.30 to $1.40. Redstone, N. H., in blocks up to 10 cubic feet, $0.75 to $1.25, averaging $0.85. Westerly, blue, in blocks up to 10 cubic feet, $1.10 to $1.15. Up to 50 to 60 cubic feet, $2.60 to $2.75. White and pink statuary, in blocks up to 10 cubic feet, $1.10 to $1.25. Up to 50 to 60 cubic feet, $2.70 to $3.25. when the Milford, Mass., pink is ordered finished for ornamental work the following prices prevail: Rock-faced ashlar building work, $1.50. Cut building work, $3.50. Polished building work, $6. Cut monumental work, $7. Polished monumental work, $10."

-

Production of

Granite by States - 1923 8 (The following is

quoted from The Commercial Granites of New England, by

T. Nelson Dale, 1923.)

-

Maine:

The quarry industry in Maine was of considerable magnitude from about 1876 to 1911 but has decreased about 50 per cent in the last 10 years. The quarries started as a result of the usual local demand, but their nearness to tidewater furnished a splendid outlet for the stone, and although New York and vicinity has been the largest market, it has been shipped to all the eastern coast cities and also by rail to Chicago, St. Louis, Atlanta, Albany, and many other interior cities. The chief use for Maine granite until recently has been for bridges, piers, buttresses, and all kinds of heavy masonry, as well as public buildings and residences. Paving blocks formerly ranked second in output, but in 1921 the amount of stone that was cut into paving block was more than twice as much as all the other stone quarried. In 1911 the the (sic) tonnage for paving blocks was about one-half as much as for the other products. About 3 per cent more blocks were produced in 1921 than in 1911, so that although the paving-block business in the State has held its own in competition with the different kinds of paving materials, the demand for all other constructional granite, including curbing and negligible amount of monumental stone, has suffered keenly from the competition of stone from other States, but chiefly from the use of concrete for buildings and foundations.

The report of the Tenth Census (1880) shows that some of the quarries in operation at that time had been opened at the dates indicated below:

Cumberland County: Brunswick, 1836.

Franklin County:

Pownal, 1860-1872.Chesterville, 1845.

Hancock County:

North Jay, 1872-1876.West Sullivan, 1840-1876.

Kennebec County:

Deer Isle, 1870-1877.

Mount Desert, 1871.

East Blue Hill, 1872-1879.

Franklin, 1879.Hallowell, 1800.

Augusta, 1856-1877.Knox County: Spruce Head, 1836.

Lincoln County:

Vinalhaven, 1850-1879.

Dix Island, 1851.

South Thomaston, 1859-1878.

Hurricane Isle, 1870.

St. George, 1874.Waldoboro, 1830.

Waldo County:

Round Pond, 1877.Frankfort (Mount Waldo), 1853.

York County:

Lincolnville, 1876.Biddeford, 1860-1868.

These dates show the beginning of the granite industry in the State, but until 1860 activity in the quarries was only local, and it was not until about 1870 that they became well known.

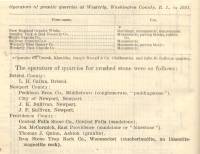

The granite quarries operated in Maine during 1921, as known to the United States Geological Survey, were as follows:

The Geological Survey is also informed that plans are underway by the George A. Fuller Co., New York City, to operate quarries at Hallowell ad Stonington (Deer Isle) in order to quarry stone for the courthouse in New York City, for which this company has the building contract.

-

New

Hampshire:

New Hampshire, notwithstanding its nickname "Granite State," usually ranks below Massachusetts, Maine, and Vermont in quantity of granite produced, but in 1921 it made a larger output than Vermont. Records show that stone from boulders at Concord were used in 1812 for construction of the New Hampshire State prison and in 1816 to 1819 for the construction of the statehouse, but it was in 1840 that the ledges of the famous Rattlesnake Hill were first opened. Few quarries, however, were operated until after 1860. At Milford quarries were opened in 1813, and stone was drawn by oxen to neighboring towns in 1833; but it was not until after 1851, when railroad transportation was available, that stone was shipped any distance. quarries were opened at Marlboro in 1812, at Nashua in 1822, at Fitzwilliam in 1860-1879, and at Allentown in 1876. Granite from New Hampshire, like that from Vermont, has been sold only to a small extent for crushed stone and riprap work. The demand for the product, chiefly as building and monumental stone and paving blocks, has therefore not shown the sharp changes indicated for the other States.

In 1921 granite was produced at the following localities in the State:

-

Vermont:

Records show that stone from the vicinity of Barre, Vt., was used to build houses as early as 1814. In 1824 millstones were furnished to Canadian and New England mills, and in 1833 stone was drawn from Barre to Montpelier to build the State capitol, which has recently been enlarged by stone from the same quarries. The report of the Eighth Census (1860) does not record any granite production from Vermont, but the report of the Tenth Census (1880) shows that quarries were opened at Barre as early as 1835 and 1840 and at Ryegate in 1850. The first factor in the rise of Vermont to prominence in the granite industry was the extension in 1875 of the Central Vermont Railway to Barre. In 1888 a railroad was built to the quarries, saving hauling that had been mostly done by ox teams. In 1880 the census report showed a production from Vermont of 187,140 cubic feet of granite, with a value of $59,675. In 1887 the Barre quarries produced 300 000 cubic feet of stone, valued at $225,000, and in 1888 stone valued at $276,000 was produced at Barre and $3,000 at Woodbury. The Eleventh Census (1889) showed 53 quarries in operation and an output of more than 1,000,000 cubic feet. The largest number of quarries at Barre were opened between 1882 and 1890.

The Dummerston quarries were developed in 1877. In Caledonia County quarries at Hardwick and South Ryegate were opened between 1850 and 1875, but the principal development here also took place after the building of a railroad in 1896. The Williamstown quarries were developed in 1889; the Bethel quarries in 1902 (quarries were opened here in 1868); the Woodbury quarries in 1880; and the Mount Ascutney quarries in 1906. The other quarries in the State are smaller and less known and have not had much influence on the total production. Barre has become the largest center for monumental stone in the country if not in the world. Little of the stone quarried is milled or dressed by the quarrymen, most of it being sold in rough blocks to manufacturers for dressing. The magnitude of the entire granite business in 1917 and 1918 in the Barre district is shown in the following tabular statement furnished by Athol R. Bell, secretary of the Barre Quarries & Manufacturers' Association, and published in the report on stone in Mineral Resources of the United States, 1918. The district includes Barre, Williamstown, East Barre, Montpelier, West Berlin, Northfield, and Waterbury. The years 1917 and 1918 are taken as representing more normal years than 1920 and 1921.

Mr. Bell states that 56 quarries were operated during 1918. Regarding industrial conditions in 1918, he says:

The Barre granite industry in 1918 was naturally subject to a good many of the proscriptions which necessity imposed upon nonessential industries. Our members, while realizing that the loss to them would be measurably irreparable, patriotically cooperated with the Government in sending men, many of them skilled pneumatic-tool operators, to the shipyards. In addition there was the prevailing shortage of unskilled labor at the quarries, and of course many men were with the colors.

The arduous winter of 1917-18 cut down the number of working days to 260, the average being 280. Yet the steady introduction of labor-saving machinery partially closed up the gap caused by the decimation of man power in the industry, prolonged suspensions due to extreme weather and fuel orders, and the inevitable shortage of cars.

The stone quarried at Woodbury, which is the center next in importance to Barre, is largely milled and dressed by the producer, as is the Dummerston stone. The accompanying tables and diagrams show the present depressed condition in the Vermont granite industry. The total output in 1921 was less than it was 32 years ago, with half as many quarries in operation, but the value of the product was over six times as great. The producers in 1921 were as follows:

-

Massachusetts:

Massachusetts has always been the largest producer of granite among the New England States, but on account of the large amount of low-priced products-paving blocks, curbing, crushed stone, breakwater stone, jetty stone, riprap, and other rough construction materials-supplied from the quarries, it has at times been exceeded in total value of output by Maine, and since 1906 by Vermont.

As previously stated, the real granite industry of this State began with the opening of the Quincy quarries in 1824 and the building of the Bunker Hill Monument and the railway or tramway from the quarries to tidewater. The development of quarry methods from quarrying and handling by hand power to the hand derrick, the application of steam t hoists, drills, pumps, etc., followed by the use of compressed air and finally electricity in both quarry and shop has been a direct result of this at that time enormous enterprise. The quarries at Quincy have been in continuous operation since they were opened. In 1837, according to Doctor Pattee's History of Quincy, the output of the Quincy quarries was 64,590 tons of stone, valued at $248,737, and there were 533 employees. In 1845 there were 526 employees, and the value of the output was $324,500. In 1865 ten quarries produced $271,880 worth of stone and employed 306 men..

Stone was also quarried at an early date at the Chelmsford quarries, but the quarries on Cape Ann-- Gloucester, Rockport, Lanesville, and Pigeon Cove-were operated soon after the Quincy quarries and from their admirable location for transportation have furnished, besides high-grade monumental and building stone, an enormous quantity of stone for river and harbor work and street work.

According to the report of the Tenth Census, quarries in operation in 1880 were opened in Massachusetts at the places and dates which are given..(in the table below)

Berkshire County: Chester (Becket), 1878-1880.

Bristol County:New Bedford, 1860.

Essex County:

Fall River, 1840-1873Rockport, 1830-1870

Hampden County:

Lawrence, 1847.

Gloucester, 1851-1878.Monson, 1839.

Middlesex County: Graniteville, 1860.

Norfolk County:

Lowell, 1876.

Westford (Chelmsford), 1845-1880Quincy and West Quincy, 1810-1879.

Worcester County:Fitchburg, 1831-1876.

Milford, 1869.

Leominster, 1872.

-

Connecticut:

The granite industry in Connecticut has declined relatively more than in any other State in New England. In the five years 1917-1921 the output decreased 65 per cent, and the production of 1921 was about one-thirtieth of that in 1889. In 1889 there were 49 quarries in operation; in 1921, 11. Much of the Connecticut granite has been used for small work, such as copings, sills, lintels, steps, foundations, cross walks, curbings, and sidewalks, and the use of concrete for work of this class has closed practically all the small quarries in the State. No granite quarries have been operated in the State for extensive riprap, breakwater, or jetty work in recent years, and this has also contributed to the decrease in output. The most important operations in 1921 were at Stony Creek, Waterford, Niantic, and buildings and monumental stone were the chief products.

The activity of quarries in Connecticut in early years is shown by the report of the Tenth Census (1880), which gave the following dates of opening of quarries in operation at that time:

Fairfield County: Greenwich, 1830-1850.

Hartford County:

Bridgeport, 1873.Glastonbury, 1850.

Litchfield County:Thomaston, 1855.

Middlesex County:Haddam, 1800. Middletown, 1830.

New Haven County:Ansonia, 1848.

Leete Island, 1870.

Stony Creek, 1878.New London County: Niantic, 1832.

Windham County:

Waterford, 1835.

Groton, 1840-1869.

Lyme, 1875-1876.East Killingly, 1842.

Sterling, 1855-1877.

Oneco, 1868.

Willimantic, 1877.

-

Rhode Island:

The granite industry of Rhode Island centers around Westerly, Washington County. Quarries were opened in this district as early as 1843, according to the report of the Tenth Census (1880), but it was after 1850 before the industry was fairly begun. In Providence County a quarry at Diamond Hill was opened in 1840, and one at Cranston in 1820. A quarry was opened at Newport, Newport County, in 1855.

There were 35 operators of quarries in 1889, and but 6 in 1921, aside from producers of crushed stone. The chief product of the Westerly quarries is monumental stone, and for this reason there was not so large a decrease in output in the five years 1917-1921 as was shown by the States where building stone is a considerable factor. A number of quarries have combined during the last few years.

-

Maine:

-

Other Economic

Considerations

- Estimating the Value of Building Stone (June 1894)The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 26, Issue 6, June 1894, pg. 135. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Foreign vs. American Marbles (October 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 10, October 1891, pg. 230. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Historical Review - 1872 - Quarries, from The Great Industries of the United States Being an Historical Summary of the Origin, Growth, and Perfection of the Chief Industrial Arts of This Country, 1872.

- Historical Review - 1923 - The Production of Granite in the New England States (From The Commercial Granites of New England, 1923.)

- Marble Production in the United States (August 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 8, August 1891, pg. 183. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Our Building Stone Supply (Conclusion) (June 1887) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 19, Issue 6, June 1887, pgs. 130-131. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- The Price of Building Stone (November 1884) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 16, Issue 11, November 1884, pg. 253. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Prices of Building Stone and Slate (January 1885) Quarrying Notes - The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 17, Issue 1, January 1885, pg. 14. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Prices of Building Stone (January 1886) Quarrying Notes - The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 18, Issue 1, January 1886, pg. 12. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Prices of Building Stone (March 1886) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 18, Issue 3, March 1886, pg. 60. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Prices of Building Stone (October 1886) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 18, Issue 10, October 1886, pg. 228. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Prices of Building Stone (February 1887) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 19, Issue 2, February 1887, pg. 36. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Quarrying Marble (July 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 7, July 1891, pg. 159. (Viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress) (photograph of quarry and quarry workers and (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Statistics of Slate Production in the United States (and distribution of slate in the United States) (February 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 2, February 1891, pgs. 37-38. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Economic Census

-

Use of Stone in Buildings,

Paving, etc.

- Building Construction, Showing the Employment of Brick, Stone, and Slate in the Practical Construction of Buildings (April 1874) (book reviews) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 6, Issue 4, April 1874, pg. 92. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Limestone Pavement (September 1878) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 10, Issue 9, September 1878, pg. 205. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- The Manufacture of Roofing Slate (February 1885) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 17, Issue 2, February 1885, pg. 38. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Slate Roofing (April 1873) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 5, Issue 4, April 1873. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Stone Pavements (July 1869) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 1, Issue 7, July 1869, pg. 194. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Stone Paving (December 1891) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 23, Issue 12, December 1891, pg. 278. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Roof Slates (October 1888) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 20, Issue 10, October 1888, pg. 226. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Slate and its Uses (May 1885) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 17, Issue 5, May 1885, pg. 109. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- The Uses of Slate in Building (January 1885) Quarrying Notes - The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 17, Issue 1, January 1885, pg. 14. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

- Uses of Slate (December 1887) The Manufacturer and Builder, Vol. 19, Issue 12, December 1887, pgs. 276-277. (Article in digital images viewed at American Memory, Library of Congress.)

1 Dale, T. Nelson. The Commercial Granites of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island - Bulletin 354, 1908, pp. 69-71.

2 Daw, A. W. and Z. W., The Blasting of Rocks in Mines, Quarries, and Tunnels, etc, pt. 1, London, 1898.

3 Methods of Quarrying, Cutting, and Polishing Granite: Mineral Industries; Eleventh Census, 1892, pp. 612-618; also Sixteen Ann. Rept., U. S. geol. Survey, pt. 4 (1894-5), pp. 446-456.

4 See Mosley, Paget, On a New Method of Mining Coal: Jour. Iron and Steel Institute, London, 1882, pp. 53-62.

5 The Commercial Granites of New England, pg. 419.

6 The Chief Commercial granites of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island, Bulletin 354.

7 The Chief Commercial Granites of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Rhode Island, Bulletin 354, pg. 213.

8 Ibid., pgs. 443-462.

Commercial use of material within this site is strictly prohibited. It is not to be captured, reworked, and placed inside another web site ©. All rights reserved. Peggy B. and George (Pat) Perazzo.